Over drinks at a bar on a dreary, snowy night in Washington this past month, a former Senate investigator laughed as he polished off his beer.

“Everything’s fucked up, and nobody goes to jail,” he said. “That’s your whole story right there. Hell, you don’t even have to write the rest of it. Just write that.”

I put down my notebook. “Just that?”

“That’s right,” he said, signaling to the waitress for the check. “Everything’s fucked up, and nobody goes to jail. You can end the piece right there.”

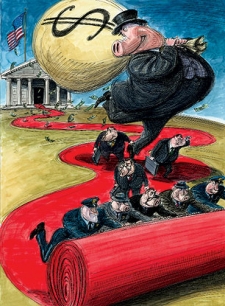

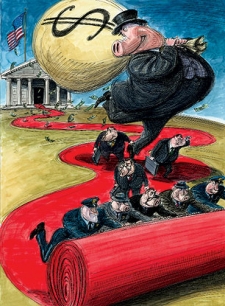

Nobody goes to jail. This is the mantra of the financial-crisis era, one that saw virtually every major bank and financial company on Wall Street embroiled in obscene criminal scandals that impoverished millions and collectively destroyed hundreds of billions, in fact, trillions of dollars of the world’s wealth — and nobody went to jail. Nobody, that is, except Bernie Madoff, a flamboyant and pathological celebrity con artist, whose victims happened to be other rich and famous people.

The rest of them, all of them, got off. Not a single executive who ran the companies that cooked up and cashed in on the phony financial boom — an industrywide scam that involved the mass sale of mismarked, fraudulent mortgage-backed securities — has ever been convicted. Their names by now are familiar to even the most casual Middle American news consumer: companies like AIG, Goldman Sachs, Lehman Brothers, JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America and Morgan Stanley. Most of these firms were directly involved in elaborate fraud and theft. Lehman Brothers hid billions in loans from its investors. Bank of America lied about billions in bonuses. Goldman Sachs failed to tell clients how it put together the born-to-lose toxic mortgage deals it was selling. What’s more, many of these companies had corporate chieftains whose actions cost investors billions — from AIG derivatives chief Joe Cassano, who assured investors they would not lose even “one dollar” just months before his unit imploded, to the $263 million in compensation that former Lehman chief Dick “The Gorilla” Fuld conveniently failed to disclose. Yet not one of them has faced time behind bars.

Invasion of the Home Snatchers

Instead, federal regulators and prosecutors have let the banks and finance companies that tried to burn the world economy to the ground get off with carefully orchestrated settlements — whitewash jobs that involve the firms paying pathetically small fines without even being required to admit wrongdoing. To add insult to injury, the people who actually committed the crimes almost never pay the fines themselves; banks caught defrauding their shareholders often use shareholder money to foot the tab of justice. “If the allegations in these settlements are true,” says Jed Rakoff, a federal judge in the Southern District of New York, “it’s management buying its way off cheap, from the pockets of their victims.”

Taibblog: Commentary on politics and the economy by Matt Taibbi

To understand the significance of this, one has to think carefully about the efficacy of fines as a punishment for a defendant pool that includes the richest people on earth — people who simply get their companies to pay their fines for them. Conversely, one has to consider the powerful deterrent to further wrongdoing that the state is missing by not introducing this particular class of people to the experience of incarceration. “You put Lloyd Blankfein in pound-me-in-the-ass prison for one six-month term, and all this bullshit would stop, all over Wall Street,” says a former congressional aide. “That’s all it would take. Just once.”

But that hasn’t happened. Because the entire system set up to monitor and regulate Wall Street is fucked up.

Just ask the people who tried to do the right thing.

Wall Street’s Naked Swindle

Here’s how regulation of Wall Street is supposed to work. To begin with, there’s a semigigantic list of public and quasi-public agencies ostensibly keeping their eyes on the economy, a dense alphabet soup of banking, insurance, S&L, securities and commodities regulators like the Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC), the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), as well as supposedly “self-regulating organizations” like the New York Stock Exchange. All of these outfits, by law, can at least begin the process of catching and investigating financial criminals, though none of them has prosecutorial power.

The major federal agency on the Wall Street beat is the Securities and Exchange Commission. The SEC watches for violations like insider trading, and also deals with so-called “disclosure violations” — i.e., making sure that all the financial information that publicly traded companies are required to make public actually jibes with reality. But the SEC doesn’t have prosecutorial power either, so in practice, when it looks like someone needs to go to jail, they refer the case to the Justice Department. And since the vast majority of crimes in the financial services industry take place in Lower Manhattan, cases referred by the SEC often end up in the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York. Thus, the two top cops on Wall Street are generally considered to be that U.S. attorney — a job that has been held by thunderous prosecutorial personae like Robert Morgenthau and Rudy Giuliani — and the SEC’s director of enforcement.

The relationship between the SEC and the DOJ is necessarily close, even symbiotic. Since financial crime-fighting requires a high degree of financial expertise — and since the typical drug-and-terrorism-obsessed FBI agent can’t balance his own checkbook, let alone tell a synthetic CDO from a credit default swap — the Justice Department ends up leaning heavily on the SEC’s army of 1,100 number-crunching investigators to make their cases. In theory, it’s a well-oiled, tag-team affair: Billionaire Wall Street Asshole commits fraud, the NYSE catches on and tips off the SEC, the SEC works the case and delivers it to Justice, and Justice perp-walks the Asshole out of Nobu, into a Crown Victoria and off to 36 months of push-ups, license-plate making and Salisbury steak.

That’s the way it’s supposed to work. But a veritable mountain of evidence indicates that when it comes to Wall Street, the justice system not only sucks at punishing financial criminals, it has actually evolved into a highly effective mechanism for protecting financial criminals. This institutional reality has absolutely nothing to do with politics or ideology — it takes place no matter who’s in office or which party’s in power. To understand how the machinery functions, you have to start back at least a decade ago, as case after case of financial malfeasance was pursued too slowly or not at all, fumbled by a government bureaucracy that too often is on a first-name basis with its targets. Indeed, the shocking pattern of nonenforcement with regard to Wall Street is so deeply ingrained in Washington that it raises a profound and difficult question about the very nature of our society: whether we have created a class of people whose misdeeds are no longer perceived as crimes, almost no matter what those misdeeds are. The SEC and the Justice Department have evolved into a bizarre species of social surgeon serving this nonjailable class, expert not at administering punishment and justice, but at finding and removing criminal responsibility from the bodies of the accused.

The systematic lack of regulation has left even the country’s top regulators frustrated. Lynn Turner, a former chief accountant for the SEC, laughs darkly at the idea that the criminal justice system is broken when it comes to Wall Street. “I think you’ve got a wrong assumption — that we even have a law-enforcement agency when it comes to Wall Street,” he says.

In the hierarchy of the SEC, the chief accountant plays a major role in working to pursue misleading and phony financial disclosures. Turner held the post a decade ago, when one of the most significant cases was swallowed up by the SEC bureaucracy. In the late 1990s, the agency had an open-and-shut case against the Rite Aid drugstore chain, which was using diabolical accounting tricks to cook their books. But instead of moving swiftly to crack down on such scams, the SEC shoved the case into the “deal with it later” file. “The Philadelphia office literally did nothing with the case for a year,” Turner recalls. “Very much like the New York office with Madoff.” The Rite Aid case dragged on for years — and by the time it was finished, similar accounting fiascoes at Enron and WorldCom had exploded into a full-blown financial crisis. The same was true for another SEC case that presaged the Enron disaster. The agency knew that appliance-maker Sunbeam was using the same kind of accounting scams to systematically hide losses from its investors. But in the end, the SEC’s punishment for Sunbeam’s CEO, Al “Chainsaw” Dunlap — widely regarded as one of the biggest assholes in the history of American finance — was a fine of $500,000. Dunlap’s net worth at the time was an estimated $100 million. The SEC also barred Dunlap from ever running a public company again — forcing him to retire with a mere $99.5 million. Dunlap passed the time collecting royalties from his self-congratulatory memoir. Its title: Mean Business.

The pattern of inaction toward shady deals on Wall Street grew worse and worse after Turner left, with one slam-dunk case after another either languishing for years or disappearing altogether. Perhaps the most notorious example involved Gary Aguirre, an SEC investigator who was literally fired after he questioned the agency’s failure to pursue an insider-trading case against John Mack, now the chairman of Morgan Stanley and one of America’s most powerful bankers.

Aguirre joined the SEC in September 2004. Two days into his career as a financial investigator, he was asked to look into an insider-trading complaint against a hedge-fund megastar named Art Samberg. One day, with no advance research or discussion, Samberg had suddenly started buying up huge quantities of shares in a firm called Heller Financial. “It was as if Art Samberg woke up one morning and a voice from the heavens told him to start buying Heller,” Aguirre recalls. “And he wasn’t just buying shares — there were some days when he was trying to buy three times as many shares as were being traded that day.” A few weeks later, Heller was bought by General Electric — and Samberg pocketed $18 million.

After some digging, Aguirre found himself focusing on one suspect as the likely source who had tipped Samberg off: John Mack, a close friend of Samberg’s who had just stepped down as president of Morgan Stanley. At the time, Mack had been on Samberg’s case to cut him into a deal involving a spinoff of the tech company Lucent — an investment that stood to make Mack a lot of money. “Mack is busting my chops” to give him a piece of the action, Samberg told an employee in an e-mail.

A week later, Mack flew to Switzerland to interview for a top job at Credit Suisse First Boston. Among the investment bank’s clients, as it happened, was a firm called Heller Financial. We don’t know for sure what Mack learned on his Swiss trip; years later, Mack would claim that he had thrown away his notes about the meetings. But we do know that as soon as Mack returned from the trip, on a Friday, he called up his buddy Samberg. The very next morning, Mack was cut into the Lucent deal — a favor that netted him more than $10 million. And as soon as the market reopened after the weekend, Samberg started buying every Heller share in sight, right before it was snapped up by GE — a suspiciously timed move that earned him the equivalent of Derek Jeter’s annual salary for just a few minutes of work.

The deal looked like a classic case of insider trading. But in the summer of 2005, when Aguirre told his boss he planned to interview Mack, things started getting weird. His boss told him the case wasn’t likely to fly, explaining that Mack had “powerful political connections.” (The investment banker had been a fundraising “Ranger” for George Bush in 2004, and would go on to be a key backer of Hillary Clinton in 2008.)

Aguirre also started to feel pressure from Morgan Stanley, which was in the process of trying to rehire Mack as CEO. At first, Aguirre was contacted by the bank’s regulatory liaison, Eric Dinallo, a former top aide to Eliot Spitzer. But it didn’t take long for Morgan Stanley to work its way up the SEC chain of command. Within three days, another of the firm’s lawyers, Mary Jo White, was on the phone with the SEC’s director of enforcement. In a shocking move that was later singled out by Senate investigators, the director actually appeared to reassure White, dismissing the case against Mack as “smoke” rather than “fire.” White, incidentally, was herself the former U.S. attorney of the Southern District of New York — one of the top cops on Wall Street.

Pause for a minute to take this in. Aguirre, an SEC foot soldier, is trying to interview a major Wall Street executive — not handcuff the guy or impound his yacht, mind you, just talk to him. In the course of doing so, he finds out that his target’s firm is being represented not only by Eliot Spitzer’s former top aide, but by the former U.S. attorney overseeing Wall Street, who is going four levels over his head to speak directly to the chief of the SEC’s enforcement division — not Aguirre’s boss, but his boss’s boss’s boss’s boss. Mack himself, meanwhile, was being represented by Gary Lynch, a former SEC director of enforcement.

Aguirre didn’t stand a chance. A month after he complained to his supervisors that he was being blocked from interviewing Mack, he was summarily fired, without notice. The case against Mack was immediately dropped: all depositions canceled, no further subpoenas issued. “It all happened so fast, I needed a seat belt,” recalls Aguirre, who had just received a stellar performance review from his bosses. The SEC eventually paid Aguirre a settlement of $755,000 for wrongful dismissal.

Rather than going after Mack, the SEC started looking for someone else to blame for tipping off Samberg. (It was, Aguirre quips, “O.J.’s search for the real killers.”) It wasn’t until a year later that the agency finally got around to interviewing Mack, who denied any wrongdoing. The four-hour deposition took place on August 1st, 2006 — just days after the five-year statute of limitations on insider trading had expired in the case.

“At best, the picture shows extraordinarily lax enforcement by the SEC,” Senate investigators would later conclude. “At worse, the picture is colored with overtones of a possible cover-up.”

Episodes like this help explain why so many Wall Street executives felt emboldened to push the regulatory envelope during the mid-2000s. Over and over, even the most obvious cases of fraud and insider dealing got gummed up in the works, and high-ranking executives were almost never prosecuted for their crimes. In 2003, Freddie Mac coughed up $125 million after it was caught misreporting its earnings by $5 billion; nobody went to jail. In 2006, Fannie Mae was fined $400 million, but executives who had overseen phony accounting techniques to jack up their bonuses faced no criminal charges. That same year, AIG paid $1.6 billion after it was caught in a major accounting scandal that would indirectly lead to its collapse two years later, but no executives at the insurance giant were prosecuted.

All of this behavior set the stage for the crash of 2008, when Wall Street exploded in a raging Dresden of fraud and criminality. Yet the SEC and the Justice Department have shown almost no inclination to prosecute those most responsible for the catastrophe — even though they had insiders from the two firms whose implosions triggered the crisis, Lehman Brothers and AIG, who were more than willing to supply evidence against top executives.

In the case of Lehman Brothers, the SEC had a chance six months before the crash to move against Dick Fuld, a man recently named the worst CEO of all time by Portfolio magazine. A decade before the crash, a Lehman lawyer named Oliver Budde was going through the bank’s proxy statements and noticed that it was using a loophole involving Restricted Stock Units to hide tens of millions of dollars of Fuld’s compensation. Budde told his bosses that Lehman’s use of RSUs was dicey at best, but they blew him off. “We’re sorry about your concerns,” they told him, “but we’re doing it.” Disturbed by such shady practices, the lawyer quit the firm in 2006.

Then, only a few months after Budde left Lehman, the SEC changed its rules to force companies to disclose exactly how much compensation in RSUs executives had coming to them. “The SEC was basically like, ‘We’re sick and tired of you people fucking around — we want a picture of what you’re holding,'” Budde says. But instead of coming clean about eight separate RSUs that Fuld had hidden from investors, Lehman filed a proxy statement that was a masterpiece of cynical lawyering. On one page, a chart indicated that Fuld had been awarded $146 million in RSUs. But two pages later, a note in the fine print essentially stated that the chart did not contain the real number — which, it failed to mention, was actually $263 million more than the chart indicated. “They fucked around even more than they did before,” Budde says. (The law firm that helped craft the fine print, Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, would later receive a lucrative federal contract to serve as legal adviser to the TARP bailout.)

Budde decided to come forward. In April 2008, he wrote a detailed memo to the SEC about Lehman’s history of hidden stocks. Shortly thereafter, he got a letter back that began, “Dear Sir or Madam.” It was an automated e-response.

“They blew me off,” Budde says.

Over the course of that summer, Budde tried to contact the SEC several more times, and was ignored each time. Finally, in the fateful week of September 15th, 2008, when Lehman Brothers cracked under the weight of its reckless bets on the subprime market and went into its final death spiral, Budde became seriously concerned. If the government tried to arrange for Lehman to be pawned off on another Wall Street firm, as it had done with Bear Stearns, the U.S. taxpayer might wind up footing the bill for a company with hundreds of millions of dollars in concealed compensation. So Budde again called the SEC, right in the middle of the crisis. “Look,” he told regulators. “I gave you huge stuff. You really want to take a look at this.”

But the feds once again blew him off. A young staff attorney contacted Budde, who once more provided the SEC with copies of all his memos. He never heard from the agency again.

“This was like a mini-Madoff,” Budde says. “They had six solid months of warnings. They could have done something.”

Three weeks later, Budde was shocked to see Fuld testifying before the House Government Oversight Committee and whining about how poor he was. “I got no severance, no golden parachute,” Fuld moaned. When Rep. Henry Waxman, the committee’s chairman, mentioned that he thought Fuld had earned more than $480 million, Fuld corrected him and said he believed it was only $310 million.

The true number, Budde calculated, was $529 million. He contacted a Senate investigator to talk about how Fuld had misled Congress, but he never got any response. Meanwhile, in a demonstration of the government’s priorities, the Justice Department is proceeding full force with a prosecution of retired baseball player Roger Clemens for lying to Congress about getting a shot of steroids in his ass. “At least Roger didn’t screw over the world,” Budde says, shaking his head.

Fuld has denied any wrongdoing, but his hidden compensation was only a ripple in Lehman’s raging tsunami of misdeeds. The investment bank used an absurd accounting trick called “Repo 105” transactions to conceal $50 billion in loans on the firm’s balance sheet. (That’s $50 billion, not million.) But more than a year after the use of the Repo 105s came to light, there have still been no indictments in the affair. While it’s possible that charges may yet be filed, there are now rumors that the SEC and the Justice Department may take no action against Lehman. If that’s true, and there’s no prosecution in a case where there’s such overwhelming evidence — and where the company is already dead, meaning it can’t dump further losses on investors or taxpayers — then it might be time to assume the game is up. Failing to prosecute Fuld and Lehman would be tantamount to the state marching into Wall Street and waving the green flag on a new stealing season.

The most amazing noncase in the entire crash — the one that truly defies the most basic notion of justice when it comes to Wall Street supervillains — is the one involving AIG and Joe Cassano, the nebbishy Patient Zero of the financial crisis. As chief of AIGFP, the firm’s financial products subsidiary, Cassano repeatedly made public statements in 2007 claiming that his portfolio of mortgage derivatives would suffer “no dollar of loss” — an almost comically obvious misrepresentation. “God couldn’t manage a $60 billion real estate portfolio without a single dollar of loss,” says Turner, the agency’s former chief accountant. “If the SEC can’t make a disclosure case against AIG, then they might as well close up shop.”

As in the Lehman case, federal prosecutors not only had plenty of evidence against AIG — they also had an eyewitness to Cassano’s actions who was prepared to tell all. As an accountant at AIGFP, Joseph St. Denis had a number of run-ins with Cassano during the summer of 2007. At the time, Cassano had already made nearly $500 billion worth of derivative bets that would ultimately blow up, destroy the world’s largest insurance company, and trigger the largest government bailout of a single company in U.S. history. He made many fatal mistakes, but chief among them was engaging in contracts that required AIG to post billions of dollars in collateral if there was any downgrade to its credit rating.

St. Denis didn’t know about those clauses in Cassano’s contracts, since they had been written before he joined the firm. What he did know was that Cassano freaked out when St. Denis spoke with an accountant at the parent company, which was only just finding out about the time bomb Cassano had set. After St. Denis finished a conference call with the executive, Cassano suddenly burst into the room and began screaming at him for talking to the New York office. He then announced that St. Denis had been “deliberately excluded” from any valuations of the most toxic elements of the derivatives portfolio — thus preventing the accountant from doing his job. What St. Denis represented was transparency — and the last thing Cassano needed was transparency.

Another clue that something was amiss with AIGFP’s portfolio came when Goldman Sachs demanded that the firm pay billions in collateral, per the terms of Cassano’s deadly contracts. Such “collateral calls” happen all the time on Wall Street, but seldom against a seemingly solvent and friendly business partner like AIG. And when they do happen, they are rarely paid without a fight. So St. Denis was shocked when AIGFP agreed to fork over gobs of money to Goldman Sachs, even while it was still contesting the payments — an indication that something was seriously wrong at AIG. “When I found out about the collateral call, I literally had to sit down,” St. Denis recalls. “I had to go home for the day.”

After Cassano barred him from valuating the derivative deals, St. Denis had no choice but to resign. He got another job, and thought he was done with AIG. But a few months later, he learned that Cassano had held a conference call with investors in December 2007. During the call, AIGFP failed to disclose that it had posted $2 billion to Goldman Sachs following the collateral calls.

“Investors therefore did not know,” the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission would later conclude, “that AIG’s earnings were overstated by $3.6 billion.”

“I remember thinking, ‘Wow, they’re just not telling people,'” St. Denis says. “I knew. I had been there. I knew they’d posted collateral.”

A year later, after the crash, St. Denis wrote a letter about his experiences to the House Government Oversight Committee, which was looking into the AIG collapse. He also met with investigators for the government, which was preparing a criminal case against Cassano. But the case never went to court. Last May, the Justice Department confirmed that it would not file charges against executives at AIGFP. Cassano, who has denied any wrongdoing, was reportedly told he was no longer a target.

Shortly after that, Cassano strolled into Washington to testify before the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. It was his first public appearance since the crash. He has not had to pay back a single cent out of the hundreds of millions of dollars he earned selling his insane pseudo-insurance policies on subprime mortgage deals. Now, out from under prosecution, he appeared before the FCIC and had the enormous balls to compliment his own business acumen, saying his atom-bomb swaps portfolio was, in retrospect, not that badly constructed. “I think the portfolios are withstanding the test of time,” he said.

“They offered him an excellent opportunity to redeem himself,” St. Denis jokes.

In the end, of course, it wasn’t just the executives of Lehman and AIGFP who got passes. Virtually every one of the major players on Wall Street was similarly embroiled in scandal, yet their executives skated off into the sunset, uncharged and unfined. Goldman Sachs paid $550 million last year when it was caught defrauding investors with crappy mortgages, but no executive has been fined or jailed — not even Fabrice “Fabulous Fab” Tourre, Goldman’s outrageous Euro-douche who gleefully e-mailed a pal about the “surreal” transactions in the middle of a meeting with the firm’s victims. In a similar case, a sales executive at the German powerhouse Deutsche Bank got off on charges of insider trading; its general counsel at the time of the questionable deals, Robert Khuzami, now serves as director of enforcement for the SEC.

Another major firm, Bank of America, was caught hiding $5.8 billion in bonuses from shareholders as part of its takeover of Merrill Lynch. The SEC tried to let the bank off with a settlement of only $33 million, but Judge Jed Rakoff rejected the action as a “facade of enforcement.” So the SEC quintupled the settlement — but it didn’t require either Merrill or Bank of America to admit to wrongdoing. Unlike criminal trials, in which the facts of the crime are put on record for all to see, these Wall Street settlements almost never require the banks to make any factual disclosures, effectively burying the stories forever. “All this is done at the expense not only of the shareholders, but also of the truth,” says Rakoff. Goldman, Deutsche, Merrill, Lehman, Bank of America … who did we leave out? Oh, there’s Citigroup, nailed for hiding some $40 billion in liabilities from investors. Last July, the SEC settled with Citi for $75 million. In a rare move, it also fined two Citi executives, former CFO Gary Crittenden and investor-relations chief Arthur Tildesley Jr. Their penalties, combined, came to a whopping $180,000.

Throughout the entire crisis, in fact, the government has taken exactly one serious swing of the bat against executives from a major bank, charging two guys from Bear Stearns with criminal fraud over a pair of toxic subprime hedge funds that blew up in 2007, destroying the company and robbing investors of $1.6 billion. Jurors had an e-mail between the defendants admitting that “there is simply no way for us to make money — ever” just three days before assuring investors that “there’s no basis for thinking this is one big disaster.” Yet the case still somehow ended in acquittal — and the Justice Department hasn’t taken any of the big banks to court since.

All of which raises an obvious question: Why the hell not?

Gary Aguirre, the SEC investigator who lost his job when he drew the ire of Morgan Stanley, thinks he knows the answer.

Last year, Aguirre noticed that a conference on financial law enforcement was scheduled to be held at the Hilton in New York on November 12th. The list of attendees included 1,500 or so of the country’s leading lawyers who represent Wall Street, as well as some of the government’s top cops from both the SEC and the Justice Department.

Criminal justice, as it pertains to the Goldmans and Morgan Stanleys of the world, is not adversarial combat, with cops and crooks duking it out in interrogation rooms and courthouses. Instead, it’s a cocktail party between friends and colleagues who from month to month and year to year are constantly switching sides and trading hats. At the Hilton conference, regulators and banker-lawyers rubbed elbows during a series of speeches and panel discussions, away from the rabble. “They were chummier in that environment,” says Aguirre, who plunked down $2,200 to attend the conference.

Aguirre saw a lot of familiar faces at the conference, for a simple reason: Many of the SEC regulators he had worked with during his failed attempt to investigate John Mack had made a million-dollar pass through the Revolving Door, going to work for the very same firms they used to police. Aguirre didn’t see Paul Berger, an associate director of enforcement who had rebuffed his attempts to interview Mack — maybe because Berger was tied up at his lucrative new job at Debevoise & Plimpton, the same law firm that Morgan Stanley employed to intervene in the Mack case. But he did see Mary Jo White, the former U.S. attorney, who was still at Debevoise & Plimpton. He also saw Linda Thomsen, the former SEC director of enforcement who had been so helpful to White. Thomsen had gone on to represent Wall Street as a partner at the prestigious firm of Davis Polk & Wardwell.

Two of the government’s top cops were there as well: Preet Bharara, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, and Robert Khuzami, the SEC’s current director of enforcement. Bharara had been recommended for his post by Chuck Schumer, Wall Street’s favorite senator. And both he and Khuzami had served with Mary Jo White at the U.S. attorney’s office, before Mary Jo went on to become a partner at Debevoise. What’s more, when Khuzami had served as general counsel for Deutsche Bank, he had been hired by none other than Dick Walker, who had been enforcement director at the SEC when it slow-rolled the pivotal fraud case against Rite Aid.

“It wasn’t just one rotation of the revolving door,” says Aguirre. “It just kept spinning. Every single person had rotated in and out of government and private service.”

The Revolving Door isn’t just a footnote in financial law enforcement; over the past decade, more than a dozen high-ranking SEC officials have gone on to lucrative jobs at Wall Street banks or white-shoe law firms, where partnerships are worth millions. That makes SEC officials like Paul Berger and Linda Thomsen the equivalent of college basketball stars waiting for their first NBA contract. Are you really going to give up a shot at the Knicks or the Lakers just to find out whether a Wall Street big shot like John Mack was guilty of insider trading? “You take one of these jobs,” says Turner, the former chief accountant for the SEC, “and you’re fit for life.”

Fit — and happy. The banter between the speakers at the New York conference says everything you need to know about the level of chumminess and mutual admiration that exists between these supposed adversaries of the justice system. At one point in the conference, Mary Jo White introduced Bharara, her old pal from the U.S. attorney’s office.

“I want to first say how pleased I am to be here,” Bharara responded. Then, addressing White, he added, “You’ve spawned all of us. It’s almost 11 years ago to the day that Mary Jo White called me and asked me if I would become an assistant U.S. attorney. So thank you, Dr. Frankenstein.”

Next, addressing the crowd of high-priced lawyers from Wall Street, Bharara made an interesting joke. “I also want to take a moment to applaud the entire staff of the SEC for the really amazing things they have done over the past year,” he said. “They’ve done a real service to the country, to the financial community, and not to mention a lot of your law practices.”

Haw! The line drew snickers from the conference of millionaire lawyers. But the real fireworks came when Khuzami, the SEC’s director of enforcement, talked about a new “cooperation initiative” the agency had recently unveiled, in which executives are being offered incentives to report fraud they have witnessed or committed. From now on, Khuzami said, when corporate lawyers like the ones he was addressing want to know if their Wall Street clients are going to be charged by the Justice Department before deciding whether to come forward, all they have to do is ask the SEC.

“We are going to try to get those individuals answers,” Khuzami announced, as to “whether or not there is criminal interest in the case — so that defense counsel can have as much information as possible in deciding whether or not to choose to sign up their client.”

Aguirre, listening in the crowd, couldn’t believe Khuzami’s brazenness. The SEC’s enforcement director was saying, in essence, that firms like Goldman Sachs and AIG and Lehman Brothers will henceforth be able to get the SEC to act as a middleman between them and the Justice Department, negotiating fines as a way out of jail time. Khuzami was basically outlining a four-step system for banks and their executives to buy their way out of prison. “First, the SEC and Wall Street player make an agreement on a fine that the player will pay to the SEC,” Aguirre says. “Then the Justice Department commits itself to pass, so that the player knows he’s ‘safe.’ Third, the player pays the SEC — and fourth, the player gets a pass from the Justice Department.”

When I ask a former federal prosecutor about the propriety of a sitting SEC director of enforcement talking out loud about helping corporate defendants “get answers” regarding the status of their criminal cases, he initially doesn’t believe it. Then I send him a transcript of the comment. “I am very, very surprised by Khuzami’s statement, which does seem to me to be contrary to past practice — and not a good thing,” the former prosecutor says.

Earlier this month, when Sen. Chuck Grassley found out about Khuzami’s comments, he sent the SEC a letter noting that the agency’s own enforcement manual not only prohibits such “answer getting,” it even bars the SEC from giving defendants the Justice Department’s phone number. “Should counsel or the individual ask which criminal authorities they should contact,” the manual reads, “staff should decline to answer, unless authorized by the relevant criminal authorities.” Both the SEC and the Justice Department deny there is anything improper in their new policy of cooperation. “We collaborate with the SEC, but they do not consult with us when they resolve their cases,” Assistant Attorney General Lanny Breuer assured Congress in January. “They do that independently.”

Around the same time that Breuer was testifying, however, a story broke that prior to the pathetically small settlement of $75 million that the SEC had arranged with Citigroup, Khuzami had ordered his staff to pursue lighter charges against the megabank’s executives. According to a letter that was sent to Sen. Grassley’s office, Khuzami had a “secret conversation, without telling the staff, with a prominent defense lawyer who is a good friend” of his and “who was counsel for the company.” The unsigned letter, which appears to have come from an SEC investigator on the case, prompted the inspector general to launch an investigation into the charge.

All of this paints a disturbing picture of a closed and corrupt system, a timeless circle of friends that virtually guarantees a collegial approach to the policing of high finance. Even before the corruption starts, the state is crippled by economic reality: Since law enforcement on Wall Street requires serious intellectual firepower, the banks seize a huge advantage from the start by hiring away the top talent. Budde, the former Lehman lawyer, says it’s well known that all the best legal minds go to the big corporate law firms, while the “bottom 20 percent go to the SEC.” Which makes it tough for the agency to track devious legal machinations, like the scheme to hide $263 million of Dick Fuld’s compensation.

“It’s such a mismatch, it’s not even funny,” Budde says.

But even beyond that, the system is skewed by the irrepressible pull of riches and power. If talent rises in the SEC or the Justice Department, it sooner or later jumps ship for those fat NBA contracts. Or, conversely, graduates of the big corporate firms take sabbaticals from their rich lifestyles to slum it in government service for a year or two. Many of those appointments are inevitably hand-picked by lifelong stooges for Wall Street like Chuck Schumer, who has accepted $14.6 million in campaign contributions from Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and other major players in the finance industry, along with their corporate lawyers.

As for President Obama, what is there to be said? Goldman Sachs was his number-one private campaign contributor. He put a Citigroup executive in charge of his economic transition team, and he just named an executive of JP Morgan Chase, the proud owner of $7.7 million in Chase stock, his new chief of staff. “The betrayal that this represents by Obama to everybody is just — we’re not ready to believe it,” says Budde, a classmate of the president from their Columbia days. “He’s really fucking us over like that? Really? That’s really a JP Morgan guy, really?”

Which is not to say that the Obama era has meant an end to law enforcement. On the contrary: In the past few years, the administration has allocated massive amounts of federal resources to catching wrongdoers — of a certain type. Last year, the government deported 393,000 people, at a cost of $5 billion. Since 2007, felony immigration prosecutions along the Mexican border have surged 77 percent; nonfelony prosecutions by 259 percent. In Ohio last month, a single mother was caught lying about where she lived to put her kids into a better school district; the judge in the case tried to sentence her to 10 days in jail for fraud, declaring that letting her go free would “demean the seriousness” of the offenses.

So there you have it. Illegal immigrants: 393,000. Lying moms: one. Bankers: zero. The math makes sense only because the politics are so obvious. You want to win elections, you bang on the jailable class. You build prisons and fill them with people for selling dime bags and stealing CD players. But for stealing a billion dollars? For fraud that puts a million people into foreclosure? Pass. It’s not a crime. Prison is too harsh. Get them to say they’re sorry, and move on. Oh, wait — let’s not even make them say they’re sorry. That’s too mean; let’s just give them a piece of paper with a government stamp on it, officially clearing them of the need to apologize, and make them pay a fine instead. But don’t make them pay it out of their own pockets, and don’t ask them to give back the money they stole. In fact, let them profit from their collective crimes, to the tune of a record $135 billion in pay and benefits last year. What’s next? Taxpayer-funded massages for every Wall Street executive guilty of fraud?

The mental stumbling block, for most Americans, is that financial crimes don’t feel real; you don’t see the culprits waving guns in liquor stores or dragging coeds into bushes. But these frauds are worse than common robberies. They’re crimes of intellectual choice, made by people who are already rich and who have every conceivable social advantage, acting on a simple, cynical calculation: Let’s steal whatever we can, then dare the victims to find the juice to reclaim their money through a captive bureaucracy. They’re attacking the very definition of property — which, after all, depends in part on a legal system that defends everyone’s claims of ownership equally. When that definition becomes tenuous or conditional — when the state simply gives up on the notion of justice — this whole American Dream thing recedes even further from reality.